Meet the goose on the move in St. Louis whose familiar name sparks ecological discoveries through its unique connection to the Saint Louis University community.

It’s not every day that you ride your bicycle up to Saint Louis University President Fred P. Pestello, Ph.D. and ask if it would be OK to name woodland creatures after him. That kind of incident has a much higher probability of happening, though, if you’re SLU biologist Stephen Blake, Ph.D. And that’s exactly what Blake did one warm spring day as he was commuting to his office on SLU’s midtown campus and happened to spot Pestello.

“The first time I stopped him and introduced myself, he was walking along in a suit and tie and a briefcase,” Blake recalled. “And here I am sweaty and unshaven. I remember saying, ‘Hi Fred. I think you are my boss’s boss’s boss’s boss.’”

After explaining that he was an assistant professor in SLU’s Biology Department, Blake said that Pestello’s eyes softened and the two stood on the west side of Grand Boulevard and chatted. After some small talk about bikes, Blake took the opportunity to describe the Forest Park Living Lab (FPLL), an urban ecology collaboration between nonprofit conservancy Forest Park Forever, The National Great Rivers Research and Education Center, Saint Louis University, the Saint Louis Zoo, Washington University in St. Louis, and the World Bird Sanctuary. The group seeks to open a window into urban wildlife and inform conservation efforts by tracking animals as they use habitats in and around St. Louis.

Because there is a significant outreach component to the FPLL — which Blake co-leads with Anthony Dell, Ph.D., from the National Great Rivers Research and Education Center and Sharon L. Deem, DVM, Ph.D., from the Saint Louis Zoo — Blake wanted to pique Pestello’s interest in the effort and increase its profile in a unique way.

“How can we draw institutional interest in this project?” Blake, who is also an associate at the Taylor Geospatial Institute, asked. “Who better than the head man?”

Blake said he thought if he could get the president of SLU publicly engaged in the project and in St. Louis’s wildlife in general, it could help him and his collaborators not only dissect how urban ecology works but to illustrate the splendor of the natural world and unlock interest and excitement in the people who share the same ecosystems. “That hopefully translates to a broader consciousness of the environment and sustainable ecological principles.”

Blake’s gambit worked. After describing his work with the FPLL, Blake asked Pestello if he could have his blessing to bestow the name “Fred” to one of the animals that the FPLL team would soon fit with a satellite tracking tag.

Of all of the unexpected requests I have received, this might have been my favorite,” said Pestello. “The Forest Park Living Lab is making exciting research advancements, and their outreach goals are inspiring. SLU is committed to advancing scientific inquiry, and to serving the greater good of our region. I was flattered by Dr. Blake’s proposal, and happy to support the lab’s innovative work.”

As they kept in touch over the ensuing weeks, the researchers’ tracking program focused on geese — Canada Geese (Branta canadensis) to be precise. Since the team wanted to tag male and female specimens of the waterfowl, Blake proposed naming a mated pair “Fred” and “Fran” after Pestello and his wife, Frances Pestello, Ph.D., the first lady of SLU and an adjunct professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology.

Pestello said he was honored by the request, and in mid-June, 2023, the team at FPLL affixed GPS-enabled collars to the slender necks of two Canada geese — Fred and Fran.

Chasing Wild Geese

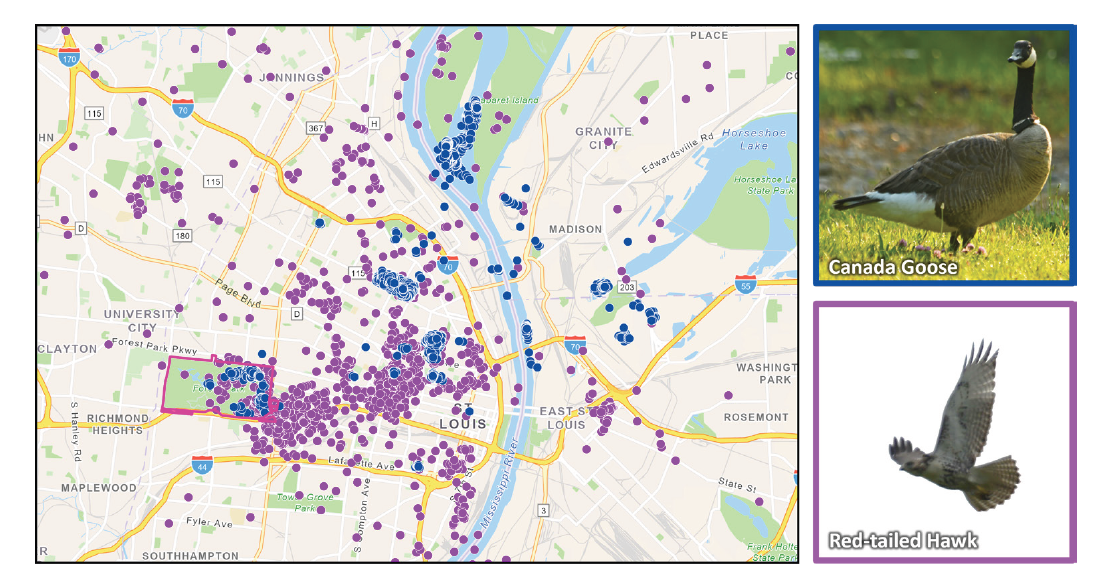

Fred and Fran (the geese) were not alone. Since the spring of 2021, the FPLL team has tagged and tracked 15 other animals, in addition to the dozens of box turtles tagged beginning in 2012 as part of the St. Louis Box Turtle Project. The animals belong to seven species, from reptiles to birds to mammals, including several raccoons, a pair of mallard ducks named Daisy and Donald, a great horned owl named Astrid, a handful of common snapping turtles, three-toed box turtles, and two red-tailed hawks named Copper and Herrmann.

Stella Uiterwaal, senior scientist at the FPLL, said that the team’s approach to urban ecology efforts is somewhat unique. “Most people who are studying animal movement or movement ecology are tracking one species, or two species if they’re getting crazy,” Uiterwaal said. But few researchers have attempted “to track so many different species all using the same space.”

Dell of the National Great Rivers Research and Education Center agrees the data the FPLL team is collecting is special. “[Urban ecology] is a very nascent field,” he said. The collaboration between so many diverse institutions and the effort to track and characterize the movements of such a wide swath of animal species coexisting in an urban landscape “really is unique globally.”

An additional novel twist of the FPLL is that team leader and wildlife veterinarian Deem — who is also director of the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine — is evaluating the health of Forest Park’s wildlife community to assess disease transmission vectors among wildlife and potentially between wildlife and humans. “Few projects bring together movement ecology along with data on the health of wildlife in urban areas to the degree our team is doing here in Forest Park,” Deem said. “Gaining an understanding of the health status and infectious disease presence of wildlife that use the Park, alongside the movement data, such as we have for Fred and Fran, is imperative to ensure both wildlife and humans may thrive in our urban ecosystems.”

Uiterwaal — a postdoctoral researcher with the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University, advised by Blake, Dell, and Deem — notes that tracking the movement of animals through an urban environment can elucidate a lot about the ecology of those areas and their animal and human inhabitants.

“Movement is really fundamental for the connections between species in communities,” Uiterwaal said. Movement determines what individuals and species encounter each other, which can result in predation, the transfer of disease, mate selection, and other ecological interactions. Researchers can garner many insights into how urban wildlife communities are structured and how they function just through understanding how they navigate and use habitats throughout a city’s landscape.

And that’s exactly the insight that Fred and Fran provided to the FPLL scientists. The researchers tracked Fred in particular as he traversed several different habitats in and around Forest Park for the three months that his tag was operational. (Unfortunately, the tag stopped sending data in late September this year. Geese, with their hard serrated beaks designed for grazing, are tough on tracking collars).

In that span of time, Fred traversed the patchwork of neighborhoods that make up St. Louis, flying from Forest Park to Fairground Park to Lafayette Square. Fred spent a large amount of his time at the water features and new lawns on the under-construction, $2 billion North St. Louis campus of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and paid visits to the Illinois side of the Mississippi River.

This brief window into the movements of a single goose (actually two geese, since we have seen Fred and Fran together on several occasions) has yielded key insights into how urban wildlife use the cities and surrounding areas they call home.

Tracking data from these two geese revealed expected patterns created by birds seeking food, water, shelter, and mates—the resources essential to their survival. But when the FPLL team overlaid those location data on a map of the St. Louis area, the patterns revealed how the human landscapes can intersect with attributes that animals like geese orient themselves to. For Fred and Fran, access to open water, such as the small lakes that dot Forest and Fairground Parks and the pond at the NGA St. Louis construction site, is a crucial component of living their best goose lives. And the grass and other vegetation that surround these urban oases provide them with abundant forage.

The FPLL researchers are gathering extraordinary data on how these seemingly disparate environs are related by observing and mapping the movements of Fred and the other animals they’ve tagged and tracked.

All of us have been astonished by how Fred has linked these areas of habitat,” Blake said. “That one individual opens a pandora’s box of mystery and new research avenues in ways that you haven’t thought of.”

Scientists usually say that you can’t say much with a sample size of one. But Fred has shown us a brand-new vision (a bird’s eye view) of the dynamic nature of urban wildlife.

Lessons from Fred

The FPLL scientists now seek to build on the data they’ve gathered from the dozen or so animals they’ve tagged and tracked. Uiterwaal said that the taxonomic diversity of their target animals can tell researchers a lot about ecological processes as they play out in urban environments, which are constantly changing. “By looking at how things like roads are impacting multiple different ecologically and phylogenetically diverse species we can get a much better understanding of urbanization,” she said. She adds that her postdoctoral work will include integrating and connecting the movement data from all the Forest Park animals her team has tagged. This will likely yield unprecedented insight into urban ecology that might inform similar efforts in other cities around the world.

In the fall of last year, just before Fred’s tag fell quiet, the team in Forest Park

was intensely tracking his movements around educational institutions in and around

St. Louis. Fred and Copper, the red-tailed hawk, seemed to take a liking to habitats

surrounding the KIPP Inspire Academy and Gateway Middle School just north of the downtown

area. Blake and his collaborators were seeking to seize on the opportunity to expose

students at those institutions to the project and interest in the science and practice

of ecology.

“Can we get out there and introduce them to Fred and get some students involved in observations of the geese?” Blake asked in an email to colleagues. “[Fred and Copper] are traversing every part of the city and visiting many schools in the region, including east Saint Louis…opening gambits for collaboration, lesson plans in STEM, training, etc.”

As outreach remains a core goal of the FPLL, Blake also said that he’s continuing to think of ways to publicize the efforts and entice more people to think about the animal communities that share the St. Louis area with its human inhabitants. And he thinks approaching people like SLU President Fred Pestello and others on the front lines of local education and awareness might be just the ticket to accomplish that vision.

For his part, Pestello said he was happy to contribute to the cause. “If lending my name to a goose can inspire young people to engage in scientific inquiry and spark interest in ecology among the broader community,” he reflected, “then I am all for it.”

Blake looks forward to extending this particular outreach strategy. This is “definitely something that we can use here,” he said.

I hope we can inspire local high school teachers or political figures to lend their interest and engagement—and maybe also their names—to this effort," said Blake.

Story by Bob Grant, executive director of communications, research.

This piece was written for the 2023 SLU Research Institute Annual Impact Report. The Impact Report is printed each spring to celebrate the successes of our researchers from the previous year and share the story of SLU's rise as a preeminent Jesuit research university. More information can be found here.