Documenting History

When the Saint Louis University School of Medicine held a virtual fiftieth-year reunion for the Class of 1970, pediatric cardiologist Paul Pitlick, M.D., (SOM ‘70) was struck with an idea: to reconnect with his graduating class, create a book of their stories, and memorialize the unimaginable progress made in medicine over a half-century.

The finished project, Our Stories: Journeys of the Class of 1970, features input from nearly 30 physicians, clinicians, and scientists—all of whom called the SLU School of Medicine home through the tumultuous years from 1966 to 1970.

Recording the Careers of the Class of 1970

From shifting social values to innovative advancements in medicine, Dr. Pitlick was inspired to document the changing face of medicine as told through his classmates’ professional biographies. “I’d lost track of most of my graduating class, and I got to thinking, ‘I bet a lot of these people had interesting lives,’” Pitlick remembers. “It’s been an amazing 50 years to be in medicine.”

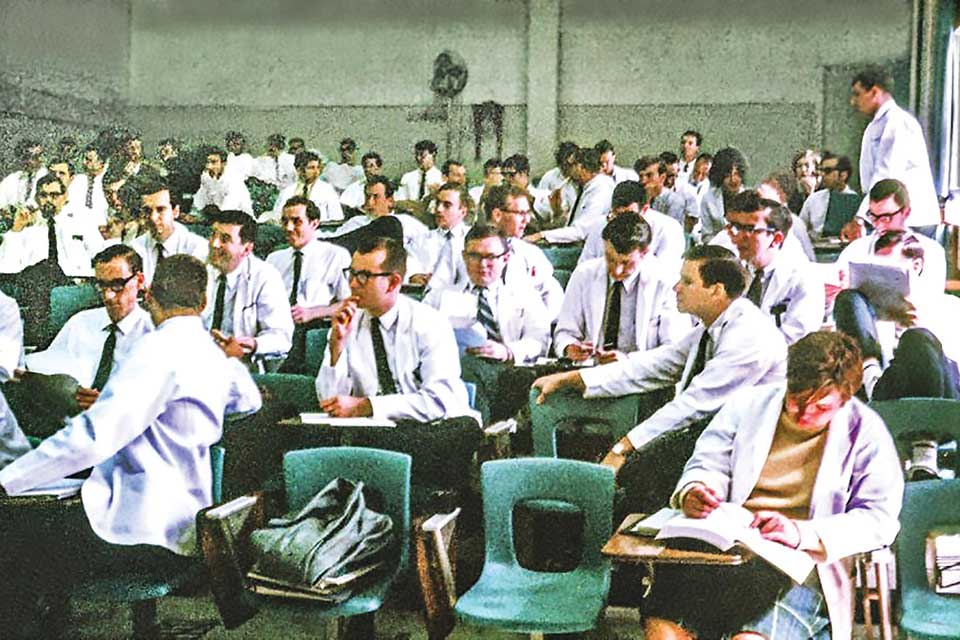

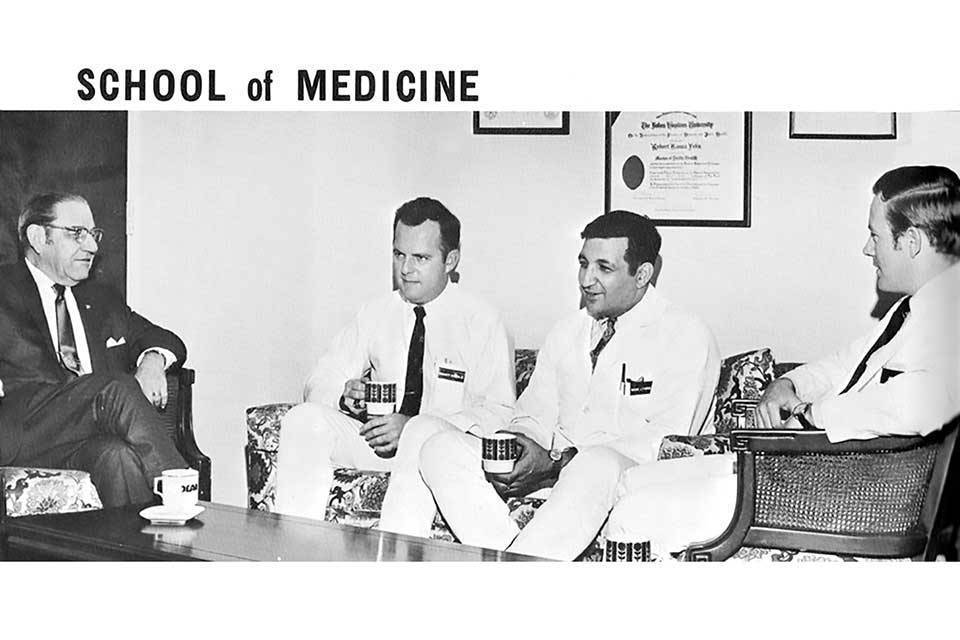

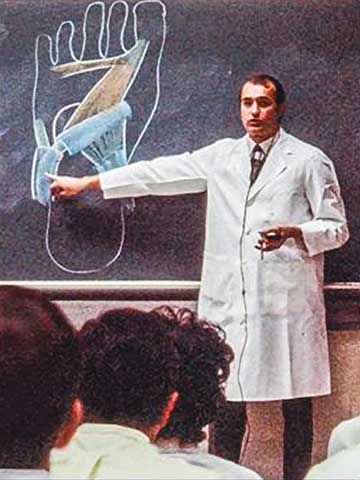

To bring his vision to life, Pitlick reached out to his former roommate, William Gruber, M.D. (SOM, ‘70), an orthopedic surgeon who, through the four years of medical school, had taken over 500 photos trying to capture students’ everyday experiences of what it was like to become a doctor. “Those slides had been stored in my basement for decades,” he recalled, “But talking with Dr. Pitlick inspired me to digitize and edit them and begin telling our story through the photo narrative that concludes the book.”

As the initial direction of the book took shape, Pitlick and Gruber began reaching out to fellow members of the Class of 1970—50 years after they graduated and began their professional lives—and asked them to write their stories.

The result? “The book is incredible,” says Gruber. “Why? Because its stories document the remarkable diversity of careers in medicine that our education made possible.” After graduation, the book details the many different paths that the Class of 1970 pursued, from depth psychoanalysts to clinical pulmonologists to lab researchers to the challenges of a medical missionary. “The book’s stories reveal the incredible spread of opportunity available when a person emerges from medical school during such a transformational era.”

Learning How to Learn

Pitlick’s own journey to becoming a pediatric cardiologist wasn’t linear. After graduating from University of Notre Dame with a degree in engineering, he realized it wasn’t the right path for him, so he opted to attend medical school.

“Most people had humanity or general science backgrounds,” he says. “But for the age that we lived in, engineering was a very good background for medicine.” With proficiency in math and science, Pitlick could grasp complicated concepts in the field of cardiology: “The signals we work with are families of sine waves,” he explains. “If you’re a mathematician, you know what a sine wave is. It turns out the stuff we learned in engineering school was very useful for cardiology.”

Reflecting on his career and his contributions to Our Stories, Pitlick recalls the most important lesson he gained from medical school came from a graduation speech by Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon, chief of surgery: learning how to learn. “The purpose of medical school is not only to learn all the stuff they were teaching us—you also had to learn how to teach yourself, because that’s how you keep up and stay on top of the field. Medical education never ends.”

With a number of technological advancements in medicine, particularly in Pitlick’s field of pediatric cardiology, the ability to continue absorbing knowledge was vital. “You have to do a lot of reading, talking to people, going to meetings, and just observing,” he shares. “Stay open to the experience. When something doesn’t seem right, ask yourself: ‘Why is that? What are we missing here?’ Developing an inquiring mind is most important.”

Navigating Unforeseeable Changes

For Gruber, a life in medicine stemmed from his fascination with living systems and a deep interest in becoming a clinician—but he encountered a number of unexpected challenges along the way. After being drafted to Korea for 13 months, Gruber built a career in orthopedic surgery. “After residency, I practiced at a conventional community hospital in Seattle for 22 years,” he says.

But in 1999, everything changed for him: “I was diagnosed with hepatitis C, which I acquired in the course of doing surgery,” he says. “At the time, it was a slowly fatal disease with no effective treatment. I was told, ‘You’ll just have to live with it.’” “Because I was infectious to patients, Hep-C ended my surgical career.”

Ten years after living with that diagnosis—and seeking new sources of meaning in life—Gruber faced whether or not to start chemotherapy. “Serial liver biopsies showed progressive liver fibrosis,” he said. “In 2009, current oral treatments weren’t available. I had to make a choice.” “I underwent a year of chemotherapy and it worked. I’ve been free of the virus ever since.”

After retiring from orthopedics, Gruber pursued a new priority: writing and teaching about the difference between curing and healing. “Curing is the objective part,” he says. “You work with data, procedures, and cognitive knowledge. But healing is the intuitive connectedness that comes from reaching out and helping another human being.”

For many of Gruber’s and Pitlick’s classmates, these personal connections with other doctors, patients, and colleagues remain a consistent highlight: “You reach a stage of life where it’s important to preserve your story and to recognize what you’ve accomplished,” Gruber says. “The choices we made, the chances we took, the care we gave our patients, and our contributions to the profession—it matters now to look back on all of that.”