Encouraging Psychological Safety to Enhance Clinical Learner Growth

Imagine you are a clinical learner. You think “not me, not me!” as the attending physician looks around the room, considering which student to call on during rounds. The attending has a reputation for being hard on medical student presentations. You are anxious and distracted by this thought, and you did not even hear his question. You make eye contact, as he points to you. Stammering, you reply in a shaky voice: “I am sorry, can you please repeat the question?”

The attending casts his eyes down, disappointed and exasperated. “Maybe a student who feels this rotation is important enough to pay attention could answer the question?” The attending sighs and promptly calls on another student.

If you are like me, you may remember a similar situation in which you felt humiliated in front of your peers during your clinical training. You may remember your self-confidence plummeting, and your motivation to learn starting to fade away. Being conscious of my own negative experiences as a student, I became interested in creating a psychologically safe environment to encourage learning for my trainees when I became an attending physician.

Even today, medical culture can tend to focus on hierarchy and power, where speaking out against someone higher in rank may be frowned upon. Psychological safety refers to an individual’s perception that they can speak openly and take interpersonal risks without consequences to their professional standing. Optimal learning can only occur when the learner feels comfortable in their environment, and feels free to explore, even if that leads to making a mistake. Without psychological safety, the learner may fear judgment, reprisal, humiliation, feelings of incompetence, and being unworthy, and, potentially, may withdraw from the learning process.

So how do trainees experience a psychologically unsafe learning environment? It can be described as an environment where learning is supposed to be the main objective, but it is not. There may be other distractions in the environment, such as excessive medical record documentation, routine patient care responsibilities, sleep deprivation from long shifts, or even the fear of making a mistake, especially in front of their attendings or peers. A learning environment can start to feel unsafe when the learner has increased awareness of how they are performing, relative to expectations. Sometimes this means “testing the waters” or withholding engagement until they feel confident that there will be no negative repercussions from speaking up, even if they are wrong or make a mistake. By contrast, a learner feels safe when they can share emotionally and intellectually without fear of retribution. A sense of safety allows the learner to explore and engage in learning opportunities.

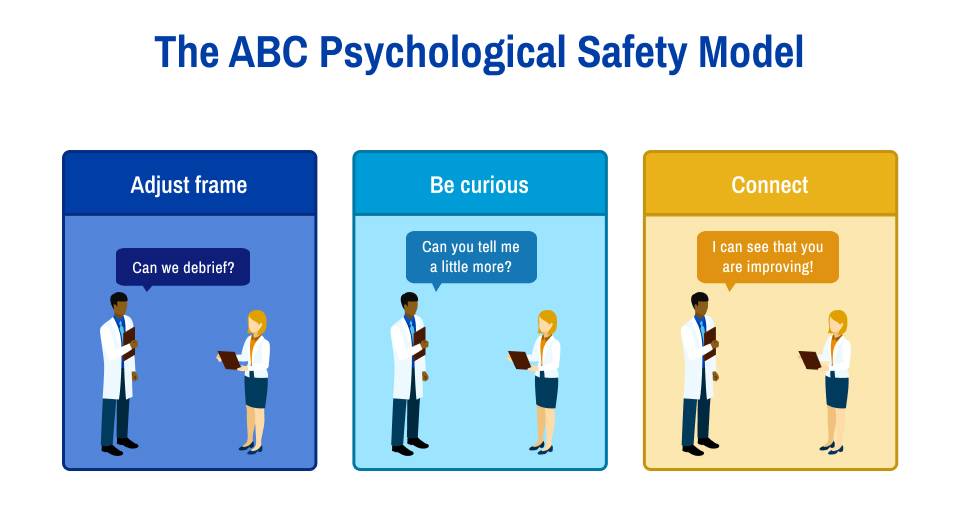

What can we do to help change decades of medical culture? One framework that has been developed for educators to establish psychological safety is the ABC model, detailed below:

A: Adjust the Frame

Be very clear about your expectations for the learner. One way you can help them understand what your expectations are is by intentionally modeling your critical thinking practice and decision-making process. For example, verbalizing out loud your decision making process when deciding on a treatment plan can help demonstrate to your learners how you take care of patients yourself. Encourage trainees to be as independent as appropriate for their level of training and be sure you express that you value their input to the team. If a mistake is made, discuss it openly with the team if it can be used as a learning opportunity, but without any judgement or making the learner feel inadequate. Discussions around mistakes should use neutral language and ideally all members of the team should participate as part of a respectful learning experience. If you are open to receiving feedback yourself, this also demonstrates a willingness to be vulnerable and will help normalize the idea that feedback can be an important tool for personal growth, no matter where you are in your learning journey.

B: Be Curious

Recognize that mistakes will happen. Approach mistakes with curiosity. All clinical learners will have knowledge gaps. Do not highlight these gaps; instead, work to fill them through evidence-based teaching practices. Intentionally recognizing similarities between us and our learners, rather than seeking to distinguish ourselves from others, can help maintain a productive focus.

C: Connect

Discuss progress with each learner and partner with them to encourage the shared goal of their personal growth. This kind of trusting relationship can be developed by treating each learner with intentional inclusivity, acknowledging varied viewpoints, and providing autonomy. Personal relationships can foster trust that you and the team are genuinely interested in their success. A strong relationship can also amplify the benefits of formative feedback. Loss of trust, on the other hand, may compromise the benefits of feedback.

Conclusion

In summary, providing excellent teaching and space for learning requires respect for our learners and their cognitive needs. Our own behaviors in the clinical learning environment can directly impact students’ perception of psychological safety in the clinical learning environment. Specific behaviors such as greeting students by name and asking them about their lives outside of medicine can help build trust and sense of belonging. Emphasizing learning and professional development as a common underlying goal in patient care can also be employed early on in team formation to create and continually cultivate psychological safety for trainees.