Episode 4: Archie Granot

Release date: Aug. 9, 2012

Max Thurm and his wife Sandra commissioned Israeli artist Archie Granot to create The Papercut Haggadah, which was displayed at MOCRA in 2012. In this episode of MOCRA Voices, MOCRA Director Terrence Dempsey, S.J., and Assistant Director David Brinker talk with Granot and Thurm about a range of topics, including how Granot was drawn to the art of papercutting, how the commission came about, the special considerations engaged in creating an artwork based on a sacred text, and continuity and innovation in the Jewish tradition.

Be sure to listen to the two Audio Extras, about the risks of working with sharp implements, and the deeper spirituality of Granot’s artistic work.

Scroll down for a Listening Guide with more information about the topics discussed.

The Conversation

Audio Extra: Dropped Blade

Audio Extra: Hiddur Mitzvah

MOCRA Voices on Stitcher MOCRA Voices on iTunes MOCRA Voices on Spotify

Related Exhibition

Archie Granot: The Papercut Haggadah

Related Episode

Stephen P. Durchslag: The Jewish Experience and the Haggadah

Credits

Producer: David Brinker

Recording Engineer and Editor: Joe Grimaldi

Host: John Launius

Listening Guide: David Brinker

Featured Guest

Archie Granot was born in London in 1946 and moved to Israel in 1967. Prior to settling in Jerusalem in 1978, he was a member of an agricultural community where he milked cows and grew melons. He earned a M.Phil. in Russian Studies from the University of Glasgow, Scotland and a B.A. in Political Science and Russian Studies from the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Granot started papercutting in 1979, and currently has his own studio and gallery in Jerusalem. Many of his papercuts carry a reminder of the Holy City, a source of his inspiration, and he often employs texts that relate to Israel, Judaism, and Judaica. Granot has had solo exhibitions in the United States, Israel, and Germany, and has participated in group exhibitions in France and Japan. Granot’s works are found in public collections in Israel, Germany, England, and the United States, as well as numerous private collections.

Listening Guide

Jump to Listening Guide for Audio Extra: Hiddur Mitzvah

| 02:40 | A moshav is a type of cooperative agricultural community found in Israel. Learn more about moshavim on Wikipedia. | |||||

| 04:20 |

It is helpful to know a bit about the structure of the Hebrew Bible. Tanakh (Hebrew תַּנַ"ךְ) is the Jewish name for the Holy Scriptures. Tanakh is an acronym formed from the initial Hebrew letters of the text's three subdivisions: Torah (the first five books of the Bible), Nevi'im (the Prophets), and Ketuvim (the Writings). Learn more about Tanakh on Wikipedia. Haftarah (Hebrew הפטרה) refers to a portion of the Hebrew Bible chanted publicly in the synagogue during Jewish religious services on the Sabbath and festivals. The haftarah reading is taken from the Prophets and follows the Torah reading, to which it is usually related thematically. Learn more about the history of haftarah on Wikipedia. You can listen to audio recordings of haftarah selections here. Typically a child chants the haftarah during their Bar or Bat Mitzvah service. See pages from the book Archie Granot created for his son's bar mitzvah. |

|||||

| 10:15 |

In contemporary usage the Hebrew word sefer (plural s'farim) can refer to any kind of book, although it often indicates books of the Tanakh, the oral law, or works of Rabbinic literature. A related word is sofer, which originally indicated a scribe but now carries the sense of writer or author. Explore a catalogue of historic and rare seforim. |

|||||

| 11:30 |

Haggadah (הַגָּדָה) is Hebrew for "telling," namely, the telling of the Exodus story at the Seder service during the Jewish festival of Pesach, or Passover. The term also signifies a book that contains the ritual guide to the Seder, along with scripture passages, commentary, prayers, and songs. For centuries the haggadah has been one of the most celebrated items of Jewish literature and art, and there are many examples of both handwritten and printed haggadot with intricate illustrations. In each generation artists continue the tradition of reinterpreting the haggadah for contemporary believers. Explore online resources about the haggadah and Passover Seder can be found on MOCRA's Papercut Haggadah exhibition website. Scroll down to the "Additional Links" section. |

|||||

| 14:20 |

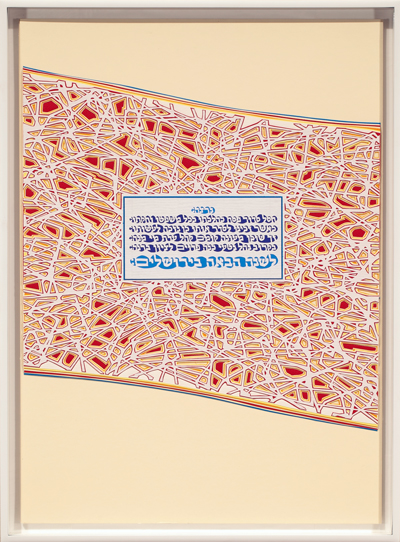

This page is "Nirtzah" ("Conclusion of the Seder"). The last line of text is the familiar phrase, "Next year in Jerusalem!" Archie Granot refers to a monthlong conflict during the summer of 2006 between the Israeli military and Hezbollah paramilitary forces. Read more about the conflict on Wikipedia. Blue and white are the colors of the State of Israel, as seen on the Israeli flag. The blue stripes recall the stripes on a tallit, or Jewish prayer shawl. |

|||||

| 16:52 |

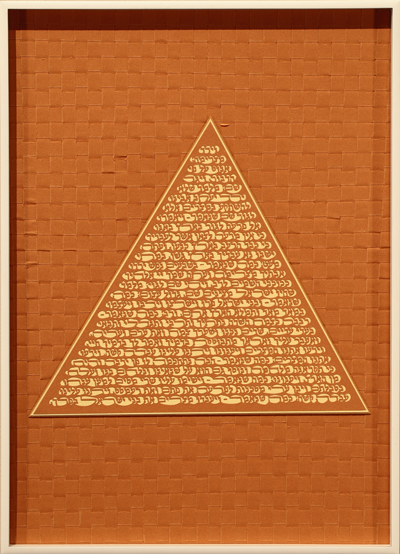

In his notes for this page, titled "Vayered Mitzraimah" ("He Went Down to Egypt"), Archie writes, "The [haggadah] text talks about the slavery in Egypt, so the pyramidal shape of the cut-out text was a natural choice. It sits on a background of paper woven by the artist, giving the impression of an unending brick wall, similar in color to the sand which, the book of Exodus tells us, the people of Israel were forced to use when making bricks." See Exodus 1:8-14 and Exodus 5:6-21. |

|||||

| 17:12 |

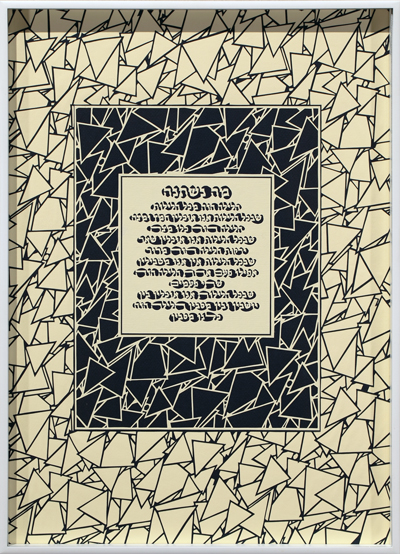

This page is titled "Bedikat Chametz" ("Searching for Leaven"). Learn more about the search for leaven on the night before Passover. |

|||||

| 17:35 |

The Four Questions (Ma Nistanah) are given this way in The Schocken Passover Haggadah:

|

|||||

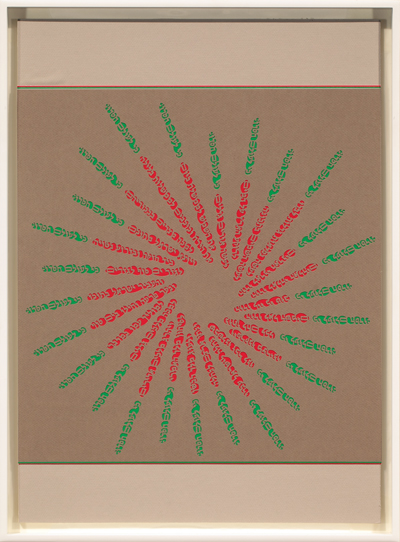

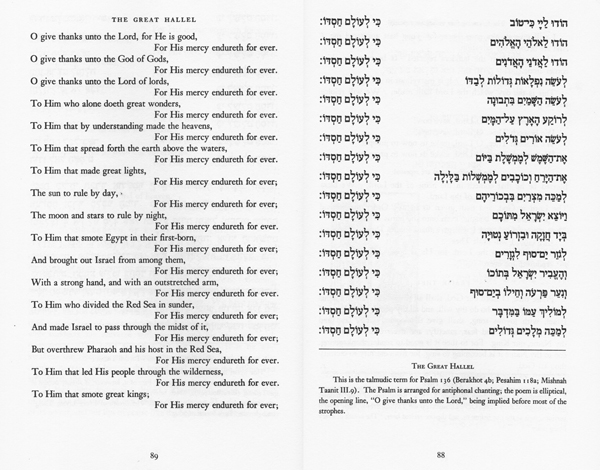

| 19:43 |

This page, titled "Ki L'olam Chasdo" ("His Goodliness Is Eternal") presents the text of Psalm 136. The recurring antiphon is set in green, the invocations in red. This image from The Schocken Passover Haggadah shows how Psalm 136 is typically typeset. |

|||||

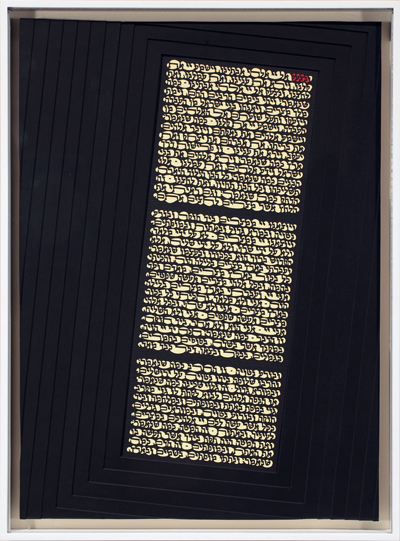

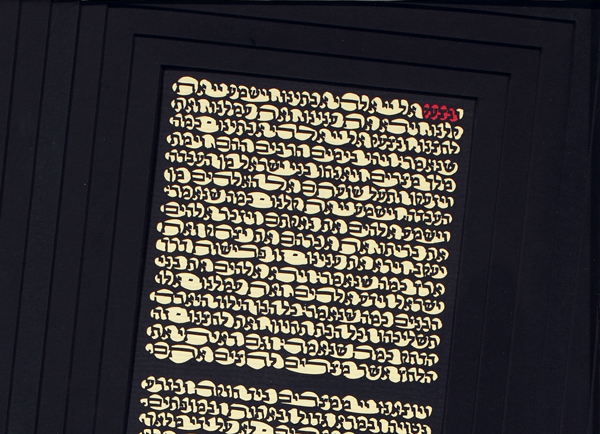

| 21:18 |

In his notes on The Papercut Haggadah, Archie Granot notes that the use of mat board in this piece was a breakthrough in the series. He says, "I wanted to capture the very depths of despair and, using board, I cut the edges and built ten layers on the left side and seven layers on the right. These numbers are very significant in Jewish thought."

The completed work measures over half-an-inch thick. |

|||||

| 25:20 | Hermeneutics is the art and science of interpreting texts. Interpretation of the Bible is its own discipline with a wide range of approaches, as discussed in this Wikipedia article on Biblical hermeneutics. | |||||

| 29:00 |

The Stations of the Cross is a set of meditations on various episodes, both scriptural and traditional, in the suffering and death of Jesus. Artistic representations in a variety of media (but usually sculpture or painting) depict each episode and help focus the meditation. Praying the Stations usually entails walking from station to station. Learn more about the Stations of the Cross in this Wikipedia article. A number of contemporary artists have reinterpreted the Stations of the Cross in their work. Examples have been included in exhibitions at MOCRA such as Consecrations: The Spiritual in Art in the Time of AIDS and Good Friday: The Suffering Christ in Contemporary Art. A major work by artist Michael Tracy at MOCRA treats three stations of the cross as a vast abstract landscape of suffering and redemption. |

|||||

| 29:42 |

Papercutting has been practiced in cultures across the world. Learn more about papercutting on Wikipedia. References to a Jewish papercut date from the 14th century, and it became an important folk art among both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. Requiring only simple and readily available tools (paper, pencil and knife), papercutting was available to all, even the poor. Traditional papercuts were highly symmetrical and featured familiar Jewish symbols as well as calligraphic inscriptions. As is evident from the example above, traditional Jewish papercuts could achieve high levels of intricacy and sophistication. They were used to fulfill hiddur mitzvah (embellishing the commandments in an aesthetic way), and could be found in homes and synagogues. This tradition almost disappeared in the first half of the 20th century, due both to emigration and to the Holocaust. During the last fifty years, however, papercut art as a means of Jewish expression has been revived. For example, the ketubah or marriage contract, which serves as a daily reminder of a couple's love, marriage vows and responsibilities to each other, is a frequent subject for contemporary papercuts. Learn more about Jewish papercutting and about ketubahs on Wikipedia. |

|||||

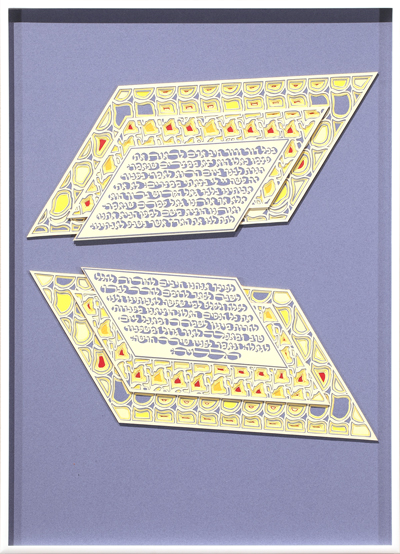

| 31:52 |

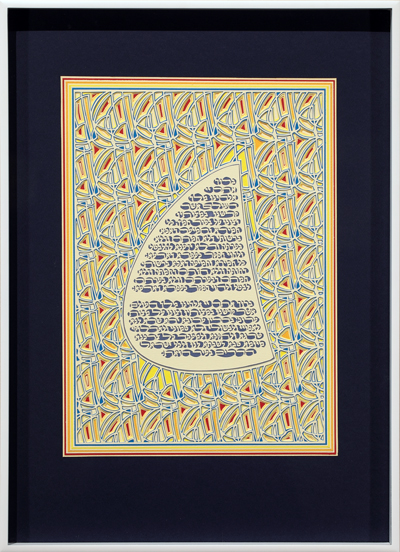

This page is titled "B'chol Dor V'dor" ("In Each Generation"). In his commentary on this page, Archie notes, "The text sits on a two-winged papercut. This papercut 'in flight' reflects the soaring spirit attained with the outpouring of praise embodied in the word Hallelujah (הּיָוּללְהַ), with which the text on this page ends. The design was created from the two initial letters of the first names of the husband and wife [Max and Sandra Thurm] who commissioned The Papercut Haggadah." Although in the podcast Archie describes this work as having 23 layers, in the commentary he gives the number as 25. The Hebrew alphabet has 22 letters, five with variant forms and all of them consonants. Vowels are indicated with marks around the letters called niqqud, or vowel points. Hebrew is written from right to left. Written Hebrew dates back more than three millennia and has gone through various stages of evolution. The present script is a stylized version of the Aramaic alphabet. Learn more about the Hebrew alphabet on Wikipedia. Hebrew typography remains a vibrant art and fertile ground for new developments, as seen in this interview about the New American Haggadah with Israeli graphic and type designer Oded Ezer. |

|||||

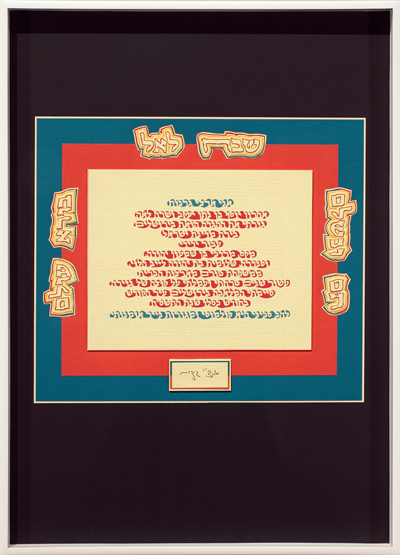

| 38:40 |

In illuminated manuscripts, the colophon (from Greek kolophōn, "summit, finishing touch") was the text which the scribe used to finish the work. A colophon might include the scribe's name, the date, and the name of the person for whom the book was made. The colophon for The Papercut Haggadah reads: I, Archie Granot The multilayered cut-out sentence around the page was, traditionally, used in colophons of Jewish manuscripts and reads: Accomplished and concluded, with thanks to the Lord, Creator of all things. The artist’s signature sits at the base of this page. It is the only signed page in The Papercut Haggadah. |

|||||

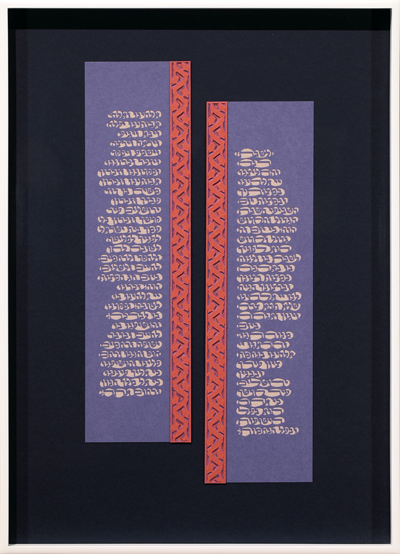

| 39:06 |

Archie Granot mentions that one page in The Papercut Haggadah incorporates his initials. It is titled, "Retze, Ya'aleh V'yavo" ("Grace after Meals: Be Pleased, May There Rise"). He notes, "The two central pillars separating these two blessings were created from the letters א (Alef) and ג (Gimmel)—my initials." Granot also mentions that three pages reference Max and Sandra Thurm. In this example, "The central image of a tower (Thurm in German, Turem in Yiddish) sits on a design created from the letter ט (Tet). The page is encapsulated by the names of Sandra and Max Thurm as well as the two verses that begin with the first and last letters of their names." For every Hebrew name, there is a corresponding Biblical verse; the first and last letters of the verse are the same as the first and last letters of the Hebrew name. It is said that memorizing this verse will help a person remember his or her name in the afterlife. |

|||||

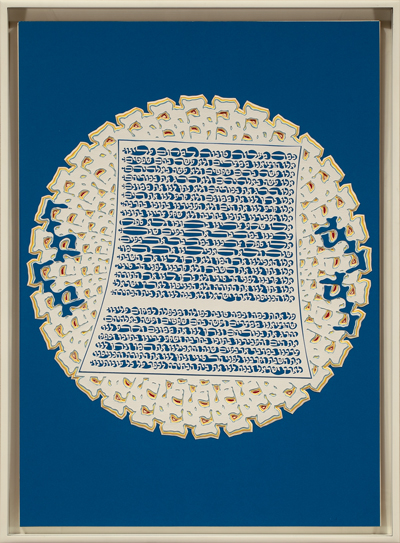

| 42:40 |

The song "Dayenu" is at least 1,000 years old. Its fifteen verses recall God's astounding acts on behalf of Israel, such as delivering the Israelites from Egypt and for giving the Sabbath and the Torah. Each verse ends with the word Dayenu, meaning "it would have been enough for us" or "it would have sufficed"—had God given only one of the gifts, it would have still been enough. Archie Granot says of this page, it "has the shape of round handmade matzah and is executed in blue and white—the colors of the State of Israel. The word Dayenu repeats itself in the circular design, in the middle of which sits the complete text of this chant." |

|||||

Listening Guide for Audio Extra: Hiddur Mitzvah

| 00:45 |

The Hebrew term mitzvah can refer to the divine commandments given in the Torah, or more broadly to moral deeds performed as a religious duty—that is, an act of human kindness. Learn more about mitzvot on Wikipedia. |

|||||