Extraordinary Archive of Civil Rights Pioneer and Judge Brings St. Louis History to Life

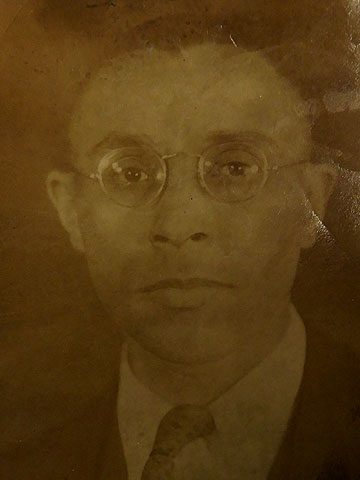

In any age, Nathan B. Young Jr. would be considered extraordinary. And Saint Louis University is helping to bring Young’s story to life for new generations of students and scholars by preserving the impressive archive of books, papers and memorabilia compiled by St. Louis’s first African-American municipal judge.

“He was genuinely a Renaissance man,” John Waide, SLU archivist emeritus, said. Waide knew the judge well, forming a bond that eventually led Young to donate his most cherished items – paintings, manuscripts and family photos – to the University. “He was a lawyer by training but he was also a historian, a folk artist, very musically inclined. He was also interested in St. Louis history and the African-American experience around the country.”

As the first African-American judge to take the bench in St. Louis’s municipal court in 1965, Young became a powerful voice for justice and civil rights in the region, even in the face of threats from the Ku Klux Klan and the horror of seeing a cross burn on his lawn. Young’s significance to the story of St. Louis’s Civil Rights movement has recently been highlighted in the Missouri History Museum’s #1 in Civil Rights: The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis.

Preserving archives like Young’s, and making them accessible to others is critical, Olubukola Gbadegesin, Ph.D., associate professor of African American Studies and art history, explained.

“Judge Young was a major advocate for educational equality, economic development and public service in black communities across the nation throughout his life,” Gbadegesin said. “His collection brings that experience into the archives of the campus. Judge Young’s works are now part of SLU’s legacy and as an institution of higher learning, it is our duty to honor this charge, preserve and engage with this archive.”

A St. Louis "Polymath"

Born in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1894, Young grew up next door to Booker T. Washington. His father, Nathan B. Young Sr. taught at Washington’s famous Tuskegee Institute and later went on to lead both Florida A&M College and Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. His son went on to earn his bachelor’s degree at Florida A&M and to attend Yale University’s School of Law where he was taught by former U.S. president William Howard Taft. The junior Young graduated from Yale in 1918 with his law degree.

Young began practicing law in Birmingham, Alabama, and became active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After working for the NAACP as an organizer, he received threats from local white supremacists.

Following his 1924 marriage to his wife, Mamie, the couple moved to St. Louis, where they raised their three children. Four years after making the Mound City his home, Young co-founded the St. Louis American, the city’s weekly African-American newspaper. He served as its publisher and an editorial writer for over 40 years.

In addition to his newspaper work, Young co-founded the Mound City Bar Association and served as an assistant city counselor for the City of St. Louis before donning a judge’s robes. He went on to receive honorary doctorates from SLU, Lincoln University and Harris-Stowe State University.

Following his 1972 retirement, Young wrote, painted and lectured. St. Louis history and folk culture combined with world issues in his artwork and writings. While self-taught, Young completed over 500 paintings and exhibited them locally and nationally.

Bonding with Billikens

Without a chance meeting, many of the artifacts that tell Young’s remarkable story might have been lost. By the 1980s, Young had spoken to his grandson’s SLU law class and had received his honorary degree from SLU in 1986. Although familiar with SLU, Young had not considered donating his archive to the University at that time, Waide explained. According to Waide, the judge discussed donating his collection to other institutions locally but those talks had ended.

Meanwhile, a visiting Harvard University graduate student, Nikola Baumgarten, who was doing research in SLU’s archives, met the judge during one of her trips to St. Louis. She went on to ask Waide, then the University’s archivist, if he would meet the judge. A tour was quickly scheduled.

“I’m almost positive that he decided that day that this was the place for him, where he felt comfortable,” Waide recalled. “He just had this good feeling coming down here.”

The tour impressed Young, who invited Waide and assistant archivist Randy McGuire to his home in North St. Louis. As the judge gave pieces of his archive to SLU, he formed bonds with the SLU archivists. Waide and McGuire would eventually help the judge by running errands, pitching in to clean up after his roof leaked and eventually finding a roofer to repair the damage. In addition to the practical errands, McGuire and Waide spent hours talking with Young and listening to his stories about his life, career and St. Louis history.

“Randy and I developed a very, very close relationship with him,” Waide said, noting that the judge never gave the archivists more than a box or two at a time as he transferred his archive. The process became part the growing bond among the men. Eventually Young’s entire archive, from full histories, family photographs, his paintings and even the case he stored his art supplies in, made their way into SLU’s archives at the Pius XII Memorial Archive. “He wanted to continue the relationship.”

Following the judge’s death, Waide received a note from Young’s daughter thanking him for helping to make her father’s last years more fulfilling. The archivist has kept the note more than 20 years.

A Legacy Lives On

Through his archive, the judge’s work is now available for a new generation to explore.

“As a scholar and teacher, it’s very rare to have such close access to work that is directly related to my area of expertise,” Gbadegesin said. “I have had amazing and productive opportunities to use Judge Young’s collection in my teaching. With this archive, students can see how important the visual arts were to such a remarkably successful professional like Judge Young. In spite of the fact that he was untrained, he still took it upon himself to use his skills, as they were, to capture important, racially-charged moments that he experienced. In looking at his paintings, I hope that students see that they should not be intimidated by the arts or by the challenges of our present day.”

“Judge Young believed in the ‘transformational power of education,’ and by preserving and teaching with his collection, we will be honoring that legacy and SLU’s own Jesuit mission,” Gbadegesin noted.

With the opening of the Missouri History Museum’s #1 in Civil Rights, The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis in March 2017, Young’s legacy is being revisited by scholars and St. Louisians. For Waide, the exhibit also offered another chance to hear from the man he came to know so well, when he stopped by the museum and listened a recording of Young housed in the exhibit.

Young’s archive is managed by the University Archives and Digital Services Unit of the Pius XII Memorial Library. Requests to view or use the collection can be made to SLU's Archives.

For questions or more information, contact Drew Kupsky, interim University archivist, librarian and associate professor, or Deborah Cribbs, senior library associate.

The Missouri History Museum exhibit runs through Sunday, April 15.

Founded in 1818, Saint Louis University is one of the nation’s oldest and most prestigious Catholic institutions. Rooted in Jesuit values and its pioneering history as the first university west of the Mississippi River, SLU offers nearly 13,000 students a rigorous, transformative education of the whole person. At the core of the University’s diverse community of scholars is SLU’s service-focused mission, which challenges and prepares students to make the world a better, more just place. For more information, visit slu.edu.

Story by Amelia Flood, University Marketing and Communications. Archival images courtesy of SLU's Archives and Special Collections. Other photos by Amelia Flood, University Marketing and Communications.