SLU Doctors Made History 50 Years Ago With First Heart Transplant in Missouri

Fifty years ago a faculty team at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine made history. On Feb. 8, 1972, a team of doctors at Saint Louis University Hospital performed the first heart transplant in the state of Missouri.

The first-ever heart transplant took place Dec. 3, 1967, in South Africa. Keith Naunheim, M.D., the Vallee L. and Melba Willman professor and chief of the cardiothoracic surgery division at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, who has been on the faculty since 1987, said four years after the initial procedure, heart transplants were far from common.

“The era of heart transplantation had begun in December 1967 when Christian Barnard performed the first successful human to human heart transplantation,” he said. “Unfortunately, the patient only lived 18 days. Over the following year in 1968, 102 transplants were performed in 17 countries. That includes transplants here in the United States performed in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York but the clinical results were underwhelming. Due to the lack of safe and effective immunosuppression regimens, prolonged survival was not the norm and enthusiasm for the operation waned over time. In 1969 there were 50 heart transplants worldwide, in 1970 only 20, and in 1971 just 10.”

Enthusiasm didn’t wane in St. Louis. At a press conference after the first surgery, Valle L. Willman, M.D., chairman of the department of surgery, said doctors at SLU Hospital had spent years preparing for the procedure.

“Dr. Willman had been working in the lab on transplantation for nearly 6 years prior to the first clinical heart transplant operation here at Saint Louis University,” Naunheim said.

Doctors were able to finally have the right conditions for a successful operation in place on the morning of Feb. 8, 1972. The recipient, a 44-year-old St. Louis man named Vincent Dobelman, had been a patient at the hospital under treatment for heart disease. The possibility of a heart transplant had been discussed, according to media reports.

The donor was a 45-year-old St. Louis man who had died in the early morning hours after surgery for a brain tumor. Surgery began at 6:45 a.m. and ended at 9:47 a.m.

Willman told reporters at the ensuing press conference the three-hour operation was performed by George C. Kaiser, M.D., professor of surgery; Hendrick Barner, M.D., associate professor or surgery; John F. Schweiss, M.D., director of the section of anesthesia and professor of surgery; J. Gerard Mudd, M.D., associate professor of internal medicine; John E. Codd, M.D., assistant professor of surgery; Richard Whiting, M.D., assistant professor of internal medicine; and Kenneth Nachtnebel, M.D., and Russell R. Kraeger, M.D., residents in surgery at the hospital, as well as a large number of others from several hospital departments. Willman coordinated the team..

At the time of the surgery, life expectancy for the recipient of a new heart was about five months. Dobelman lived 312 days following the procedure — twice as long as expected.

“The patient lived for just over 10 months and only succumbed due to a lung cancer he had developed several months postoperatively,” Naunheim said. “Still, Dr. Willman helped validate the concept that prolonged survival was achievable and that was the beginning of a long transplant experience here at Saint Louis University.”

During the press conference following the surgery, the SLU team didn’t make the procedure sound like a big deal. Willman told reporters, “We don’t look at this as any great thing” and commented that other procedures were more difficult. Fifty years later, Naunheim, who is also a SLUCare cardiothoracic surgeon, disagreed with his former colleague, who passed away in 2009.

“It is not surprising that it was downplayed by Dr. Willman,” Naunheim said. “While humility is not a common characteristic for most heart surgeons, Val Willman was one of the humblest and least self-aggrandizing doctors I have ever met. The heart transplant was indeed a huge deal at the time.”

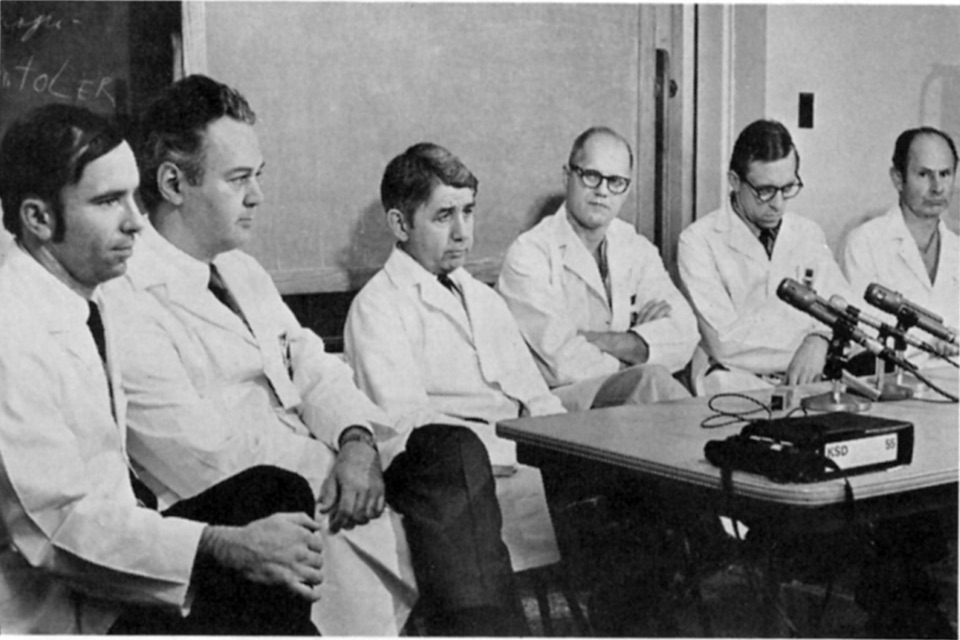

At the press conference, a photo was snapped of some members of the team. The photo has been on the desk of Laura Taylor Bianchi, program coordinator with the General Surgery Residency Training Program, for years. Bianchi, who has been with SLU for more than four decades, worked with many of the doctors, called the picture one of her most prized possessions.

“I knew Dr. John Schweiss from the anesthesiology side of our department, but I worked directly with Drs. Val Willman, George Kaiser and Rick Barner as part of the office staff,” Bianchi said. “They were the foundation of the Cardiothoracic Surgery Division and orchestrated a landmark procedure. It was an honor to work with them.”

Bianchi said the doctors in the photo “built the cardiothoracic program at SLU.”

“There was constant research and development of new techniques,” she said. “There were numerous publications in medical journals and textbooks, presentations at national and international conferences, yet they were so humble about it. Everything they did was 'just another day at the office.' It was an extremely busy and exciting time. I would love for all SLU medical students and Surgery Residents to know whose shoulders they're standing on.”

Naunheim, who also worked with many members of the original transplant team during his time at SLU, also spoke highly of the group. Despite the history making procedure, he said the topic rarely came up.

“As junior faculty, I heard relatively little about that first heart transplantation experience,” Naunheim said. “One might chalk that up to humility, but I really think it’s as much a generational response as any individual characteristic. World War II veterans are often referred to as members of ‘the greatest generation’ and so many of them did not like discussing their experiences in the war.

“They felt they were just a member of the greater community that were doing their jobs and that it was unseemly and unnecessary to highlight their own actions. Drs. Willman, Kaiser and Hanlon were certainly members of that generation and it was not customary for them to regale people with tales of their own success or achievement. They truly considered themselves ‘nothing special’ and felt they too were just doing their jobs. It was an honor to work with men of such character.”

Thanks to the work of the early heart transplant doctors, including the SLU team, the life expectancy for heart transplant recipients is much longer.

“Over the past five decades, the transplantation community has become much better at selecting appropriate candidates, performing a safe implantation procedure, monitoring for and managing rejection episodes,” Naunheim said. “This has led to prolonged periods of survival that were just not possible in the early days of heart transplantation.”

The SLU doctors were pioneers in the area of cardiac surgery, Naunheim said.

“Drs. Kaiser, Barner, Willman and Hanlon were present during and participated in the earliest stages of cardiac surgery,” Naunheim said. “In its nascent phase, heart surgery was both thrilling and a difficult enterprise for all involved. Operative techniques and technology were being devised, refined and sometimes discarded sometimes within a few weeks to months. Heart lung bypass technology had just been introduced and was still somewhat rudimentary. The surgery was complex, difficult and, frankly, somewhat dangerous. The only reason patients agreed to such surgery was that they otherwise faced severe disability and or the prospect of an early death.”

Naunheim said being pioneers had its drawbacks. Advancements often came with setbacks. Death was a relatively frequent occurrence for surgeons to deal with.

“To take on the psychological burden of operating in such an environment required not just extraordinary technical skill but a remarkable amount of fortitude and responsibility,” Naunheim said. “It’s not easy to walk into the OR everyday questioning whether you can really pull the patient through a 6 hour long operative struggle and defeat the specter of what would otherwise be a fatal disease.

“These guys were truly pioneering in the realm of heart surgery and it was an honor to work with them and be considered their colleague.”