SLU Legends and Lore: The Heithaus Homily

Note: This story contains language in direct quotes that was considered appropriate historically, but that is not acceptable today.

The student Mass on Friday, Feb. 11, 1944, began like any other.

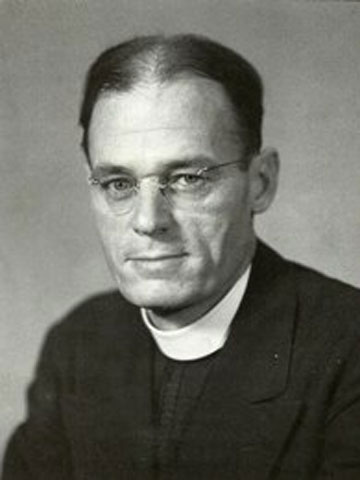

But as the liturgy’s presiding priest, Clause Heithaus, S.J., began his homily, the words the Jesuit spoke would change the course of Saint Louis University’s history, opening its doors to African-American women and men who had previously found SLU closed by racism and segregation.

Before 500 congregants, Heithaus confronted racial prejudice head-on saying, “to some followers of Christ, the color of a man’s skin makes all the difference in the world.”

“Our Lord and model, Jesus Christ, commanded his followers to teach all nations,” the 46-year-old assistant professor of archaeology continued. “Saint Louis University admits Protestants and Jews, Mormons, Mohammedans, Buddhists and Brahmins, pagans and atheists, without even looking at their complexions. Do you want us to slam our doors in the face of Catholics because their complexion happens to be brown or black?”

Calling on the students gathered at the Mass to reject racism, Heithaus’s homily would become the clarion cry that led to the first integration of a university in a former slave-holding state later that year.

A ‘Classical’ Jesuit

Born in St. Louis on May 28, 1898, Claude Heithaus grew up south of SLU, attending St. Francis de Sales Grade School and Loyola Hall High School. As a SLU undergrad, Heithaus managed the Archive, the University’s yearbook and The Billiken, the forerunner to today’s University News. A member of the SLU football team, Heithaus was also active in clubs across campus.

Following a short tour in the U.S. Army during World War I, Heithaus returned to SLU to complete a degree in classical languages in 1920. After graduating from SLU, he entered the Society of Jesus.

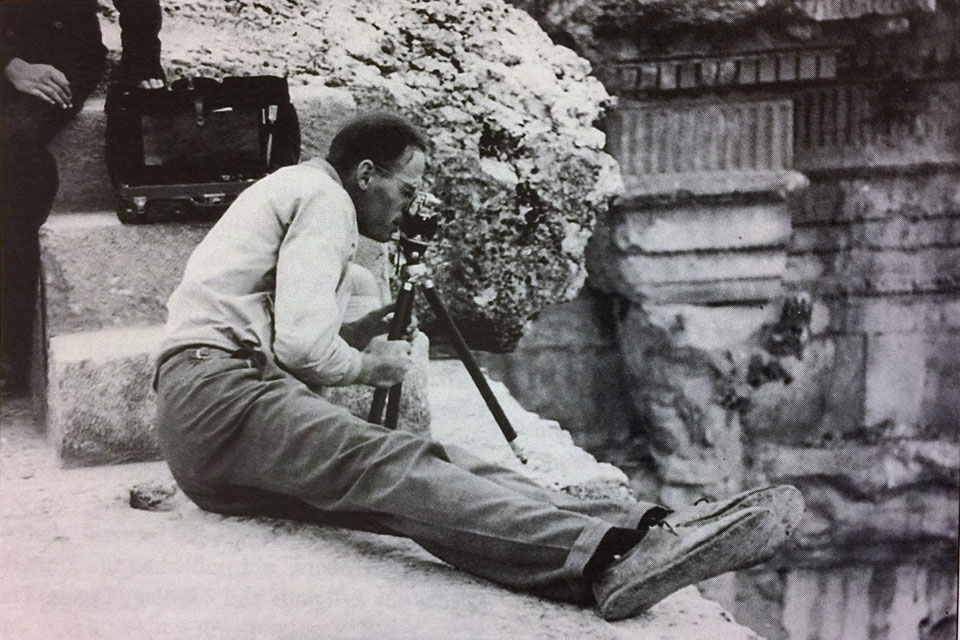

In 1921, Heithaus was sent to Europe to complete graduate work studying classical art and archaeology at University College at the University of London. While completing his doctorate, the young Jesuit took part in several archaeological digs in the deserts of Syria and Lebanon.

After years teaching in the Department of Classical Languages at the University of Detroit, Heithaus returned to St. Louis in 1930 and was ordained a priest by St. Louis Archbishop John J. Glennon.

Now a member of the faculty, Heithaus advised The University News while teaching as an assistant professor of archaeology. Heithaus also put together exhibits featuring artifacts he had collected during his graduate work. He dreamt of resurrecting the University’s history museum in DuBourg Hall.

SLU in Slavery’s Shadow

Like the St. Louis area at large, SLU was deeply marked by slavery’s legacy.

Enslaved people journeyed with the first Jesuits who made their way from Baltimore to St. Louis. Women, men and children had suffered in service to the University and its students from its founding in 1818 through to the end of legal slavery in St. Louis after the Civil War.

Anti-literacy statutes passed in the decades leading up to the Civil war had prohibited teaching African-Americans to read and write. However, abolitionists like Pastor John Berry Meachum, and his wife, Mary, resisted the strictures, creating clandestine schools including a “Floating Freedom School” on a steamboat in the middle of the Mississippi River.

With slavery legally abolished in Missouri, social segregation took its place. African-Americans were barred from most white businesses and institutions. By 1944, all Catholic grade and high schools in St. Louis were segregated. Only two St. Louis Public Schools’ high schools served African-American students.

SLU and other local colleges and universities did not admit Black students by custom, not by law.

A Homily Builds on a Legacy of Activism

While segregation pervaded all corners of St. Louis life, activists, including Jesuits, pushed back.

In 1873, Ignatius Panken, S.J., a Jesuit with ties to SLU, formally established St. Elizabeth’s Parish just north of the University. His work continued under two “radically progressive” Jesuits, the Markoe brothers, John and William, who were outspoken critics of racism and segregation. The brothers were especially interested in working with young African-Americans, organizing the parish’s “Young Catholic Crusaders” group.

SLU Jesuit Daniel Lord, S.J., director of the Sodality, a major Catholic youth organization, worked with young St. Elizabeth’s parishioners on music and drama. Lord invited the students to attend his popular Summer School for Catholic Action programs on the campuses of Catholic colleges and universities across the nation. Several programs took place at SLU, informally and quietly integrating the campus in the years leading up to Heithaus’s speech.

In the two years leading up to Heithaus’s 1944 homily, University President Patrick Holloran, S.J., had sent a letter to a number of St. Louis groups to get a sense of how the community would react if the University began admitting black students.

Jesuit leadership both in the Missouri Province and at the University considered admitting African-Americans to schools under the Province’s control.

Speaking Truth to Racism’s Power

As Heithaus continued speaking at the Feb. 11 Mass, his homily became an eloquent, yet firm, denunciation of racial intolerance and injustice.

“And now I ask you Catholic students to look at the Blessed Sacrament and answer this question,” Heithaus asked those gathered. “Will you not do something positive right now to make reparation for the suffering which this prejudice has inflicted upon millions of your fellow Christians?”

Noting his horror at how African-Americans had been treated by their fellow Catholics, Heithaus went further. He asked the students present to join him in taking a prayerful, yet direct, action.

“For the wrongs that have been done to the Mystical Body of Christ through the wronging of its colored members, we owe the suffering Christ an act of public reparation,” the Jesuit said. “Let us make it now. Will you rise please? Now repeat this prayer after me. ‘Lord Jesus, we are sorry and ashamed for the wrongs that white men have done to Your Colored children. We are firmly resolved never again to have any part in them, and to do everything in our power to prevent them.’”

Prior to the Mass and his homily, Heithaus had made certain that there would be coverage and reporting of his remarks. As faculty advisor to The University News, he had provided the newspaper’s printer with a copy of his remarks before Mass. He also invited an editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to the Mass and had reserved a place for him in the choir loft of the church.

Shattering Segregation at SLU

The Post-Dispatch covered Father Heithaus’s homily both on its front and editorial pages on Feb. 11, 1944. The University News printed the entire homily in its edition the same day.

Controversy erupted. Holloran reprimanded Heithaus, telling him that the homily was now being viewed as the University’s new official policy. Other church leaders, including Archbishop Glennon, were also critical, letting Heithaus and Holloran feel the full force of his anger and disapproval in an in-person meeting shortly after the homily.

Heithaus was told not to speak publicly again about the issue of racial integration.

However, he spoke out again in a March 1945 essay in The University News, criticizing SLU leaders for their attempts to walk back from integrating the University fully.

He was reprimanded again by his superiors. He was sent away from SLU, first to Fort Riley, Kansas, and later to Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was told not to speak about racial justice issues again.

However, Heithaus’s words had shattered segregation’s hold on SLU. On April 25, 1944, Zaccheus Meyer, S.J., the Jesuit Assistant for the United States, instructed Holloran to admit black students to the University.

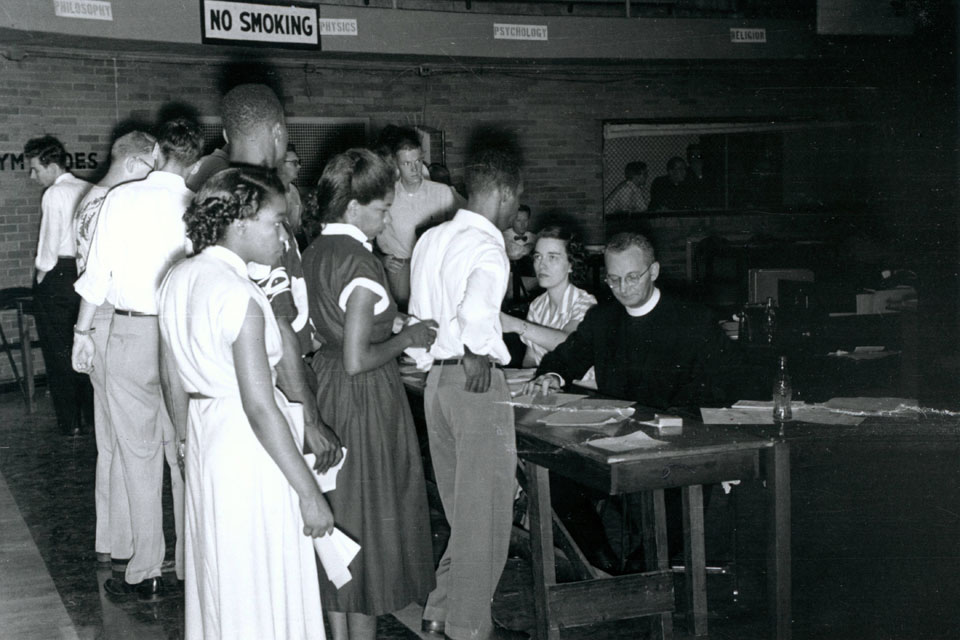

SLU’s first African-American students, two undergraduates and three graduate students, enrolled to begin classes that summer. When the new Billikens began coursework, their presence marked the first time a college or university in any of the 14 former slave-holding states had integrated. As they began their college journeys, the five were the first to integrate any school of any level in the City of St. Louis.

Homily Becomes a Continued Call to Work for Justice

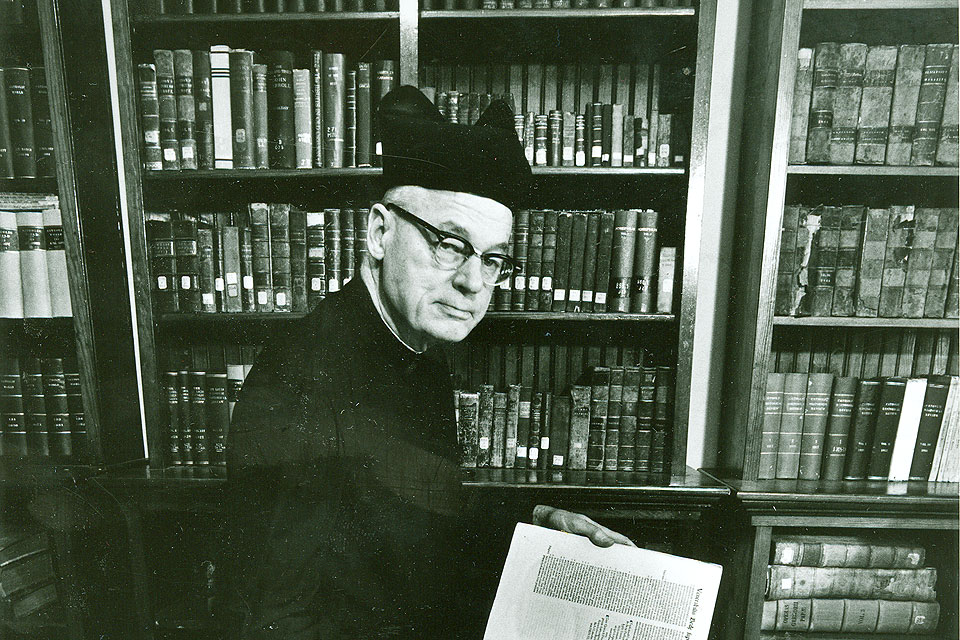

Heithaus would return to SLU in 1958. He would teach in the Department of Classical Languages in the College of Arts and Sciences before later becoming curator of the Jesuit museum established at the former St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant.

He died in May 1976, shortly before his 78th birthday.

In the decades since 1944, Heithaus’s words have become a touchstone as the SLU community continues its work toward racial equity, inclusion and restorative justice.

After 200 years, there are many legends and untold tales hiding in the nooks and crannies of Saint Louis University. Delve into the myths, fables, fantastic lives, moments and surprises you will find in its story with “SLU Legends and Lore.”

Story based on the "SLU Legends and Lore" Bicentennial Series by John Waide, University archivist emeritus. Photos courtesy of the Saint Louis University Archives. Story by Amelia Flood, University Marketing and Communications.