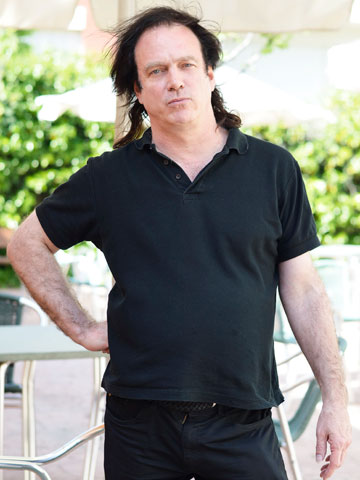

Write Stuff: Brian M. Goss, Ph.D.

Learn about the projects and passions of SLU faculty and staff members who have written books, in their own words.

After an "epiphanic" moment during a guest lecture about the Iraq War's impact on civilians, Brian Goss, Ph.D., switched from studying psychology as an undergraduate to communication, politics and media, a choice that put him on a path to a doctorate and faculty role at SLU-Madrid. Now teaching in the country he fell in love with more than 20 years ago, Goss studies "flak" a political strategy that increasingly colors political conversations on both sides of the Atlantic.

His new book, The Rise of Weaponized Flak in the New Media Era: Beyond the Propaganda Model, is forthcoming from Peter Lang Publishing. Goss is also the author of 2013's Rebooting the Herman & Chomsky Propaganda Model in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Peter Lang Publishing) and Global Auteurs: Politics in the Films of Almodóvar, Winterbottom and Von Trier, also published by Peter Lang Publishing in 2009. He has co-edited two anthologies and authored numerous articles and chapters.

Flak describes a political strategy of harassment. Distinct from the more widely-known "scandal," flak, in Goss's view, is a multifaceted weapon that, while taking on personal dimensions ultimately furthers a political and/or ideological goal.

"My conviction is that if we do not even have a name for the practices of flak, backed with a reasonably elaborate characterization of it, we are far more vulnerable to its egregious tactics and strategies," Goss said.

His new book is a first-of-its-kind study and he has presented on the project in Spain, Belgium, Romania, the United Kingdom and in the Czech Republic among other countries. Goss is set to speak on flak at Erasmus University in Holland in 2020.

I grew up around Boston in the 1970s in an environment dominated by playing baseball (New England climate permitting) and following the Red Sox — a milieu permeated with Carl Yastrzemski, not Karl Popper or Karl Marx.

At Wesleyan University in Connecticut, I pursued an undergraduate degree in psychology and continued graduate study at the University of Illinois. On one hand, I had doubts that I could abide the regimen of a career laboratory geek.

And, on the other, I heard former United States Attorney General Ramsey Clarke speak in Urbana in March 1991. He described, in eye-witness detail, the civilian impact of the US bombing campaign in Iraq that had just concluded. It was a jarring epiphanic moment, as the news accounts that I had read largely occluded the scale of the civilian impact of the military campaign. In short order, I pivoted to graduate study in communication with a concentration in politics and media and a minor in Popular Culture; mass media, in other words.

In the mid-1990s, I also visited Spain for three weeks and was blown away by everything about the country; from Spaniards’ general sociability and knowledge about the world outside their own country, to dress, food and drinking practices.

When I had an offer from SLU in Madrid in 2001 following a year-long stint as a non-tenure track instructor at Illinois, I seized it with both hands.

The Rise of Weaponized Flak is concerned with what can be expressed in the brutal concision of two words as "political harassment" that far exceeds usual lines of criticism. Flak is backed with power and strategically concerned with realizing outcomes that advance that power through delegitimizing and disabling people, organizations and sociopolitical causes perceived to contradict its interests.

Moreover, flak is distinct from the more widely-circulated term scandal, since scandals revolve around ascertaining the truth about apparent wrongdoing. By contrast, flak advances heated claims and incites actions without reasonable cause to assume wrongdoing on the part of flak targets; accusation collapses into conviction toward getting that person disciplined or fired, this organization disbanded, or some cause discredited.

In the book, I define flak as a weapon of bad faith actors backed with power: "Flak is enacted by powerful entities — or backed by powerful players in the wings — toward consequential sociopolitical objectives. It is distinct from good faith criticism (of a speech, of a bill) as well as from scattershot trolling against whomever is convenient. In this view, flak is a multidimensional form of weaponized political activity intended to attract notice, while it impedes or abolishes the effectiveness of its targets. Flak strategies and tactics toward these ends are not simply expressions of personal antipathy, but are driven by purposeful, ideologically-defined goals with tangible impact in the sociopolitical domain."

The contrived arm-waving around Barack Obama’s birth certificate is a straightforward case of flak mobilized in order to arouse indignation and delegitimize its target—a campaign that was indifferent to (indeed, weirdly fueled by) lack of evidence.

Given that no previous volumes have been published on flak, the book features two introductory chapters (about a quarter of the text) to flesh out a theory of flak including its subtypes. The balance of the book is organized around case-studies.

The first two case studies address "flak mill" organizations that are dedicated to producing flak against, for example, climate science, regulation of the capitalist economy, genuine scientific inquiry, and the center-left in general.

The second set of case studies orient toward flak at particular issues: notably, flak against the electoral process (for example, the miserable “massive voter fraud” flak charade) and against higher education.

I only address "fake news" briefly in the book because it is not an especially useful term. As the United Kingdom’s House of Commons (UK) Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee concluded in 2018 in Disinformation and Fake News, fake news may encompass everything from prosocial satire in The Onion to pernicious stories made up from whole cloth. It is a wildly imprecise term.

Moreover, "fake news" has also been increasingly hijacked by the very purveyors of what may be construed as its most socially corrosive forms in order to flak at realities that do not unswervingly serve them. Fake news is a confused term at best, thus I focus on flak as it always conveys a criticism of what is thusly characterized.

Although flak is not new — Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky incorporated the term into their "propaganda model" in 1988 — it is safe to say that its practices have hypertrophied in the new millennium. At the same time, I have often felt compelled as an academician to investigate unpleasant matters and the underside of the sociopolitical scene, while pursuing the proverbial permanent opposition to the status quo.

Every week, there are new developments that merit attention from a flak perspective. While I was writing the book’s "Introduction" in January, Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation released the Roger Stone indictment that had implications for what I was writing about weaponized flak in political campaigns via illegal and selective "hack and flak" of confidential materials.

Last week, several members of the United Kingdom parliament openly discussed the level of abuse they now routinely confront, up to threats of violence (that are not protected speech, and thus hurtle beyond flak into criminality).

The upshot is that the sociopolitical arena is becoming a more-viscous, mean-spirited place. One wonders whether the best or the brightest will be attracted to inserting themselves into this milieu, given that the human psyche was not designed to withstand global derision. If one objective of contemporary rightwing flak is to attack the pillars of governance and summon a law-of-the-jungle world, this is one path by which to push for a more caveman-like vision of politics and society. The stakes are high; our better, collective tendencies must prevail.My training and methods do not implicate a genealogy of flak. I have adopted the term from Herman and Chomsky’s previously flagged "propaganda model" that they introduced in Manufacturing Consent (1988). In turn, Herman and Chomsky do not much dwell on flak, nor do they theorize it to any appreciable degree.

Across the three decades since the introduction of Herman and Chomsky’s model, the new media environment has made it far easier to fabricate and circulate flak in all directions. At the same time, prior to my volume, there has been no book-length treatment of flak as political harassment.

If one looks in Amazon (an effectively exhaustive source), all of the entries on flak refer to World War II anti-air craft activity, not political harassment!

I first published on flak in 2009 in Journalism Studies and devoted a chapter to it in a 2013 book entitled Rebooting the Herman & Chomsky Propaganda Model in the Twenty First Century. I had also picked up a new course, Communication 3060/Political Communication, in 2010. As I covered flak and the propaganda model each semester in the course, I was also developing concepts and case-studies that lent themselves to book-length treatment. In other words, the book clearly pirouettes between teaching and research that inform, shape and sharpen each other.

I have done a good deal of research on Spain that includes examination of the country as represented in international press, Spain’s films and film directors including Pedro Almodóvar, Jaume Balagueró, Alberto Rodríguez), prensa rosa (“pink press”) women’s magazines, and Spain’s regional tourism discourses.

Thanks to my colleague Joan Pedro Carañana, Ph.D., I also have a chapter on flak that will appear in a volume on the propaganda model and reach Spanish-speaking scholars. I will make the shout-out here to my colleague Rosana Vivar, Ph.D., who rigorously copy-edited my chapter as I am decisively not a native Spanish speaker — but her efforts made me sound like one in print.

That said, The Rise of Weaponized Flak largely (but not exclusively) employs case-studies and examples from the USA as I know its political backstory in finer-grained detail. In the book, I develop a case study of the impeachment of, for example, Dilma Rouseff in Brazil in order to make the point that flak methods are portable and can readily be exported across borders.

While there is appreciably less “free speech” absolutism in Europe, flak can readily blow across borders. When I spoke at University of Antwerp in Belgium in April, for example, many of the people on hand to hear about flak were from local government in the city and in Flanders. They told me that they attended because they were very concerned about the direction that some tendencies in Europe’s political discourse have been taking.

Just as the propaganda model is now being researched vis-à-vis its applications outside the USA where is was developed, flak should be studied within national ecosystems by people who know much more than I do about the deep context of those national ecosystems. I am making an effort to put the term flak into wider circulation and hope that other researchers and members of the public will seize on it in the spirit of critical inquiry.

The book is much stronger on diagnosis than prescription. I unpack flak campaigns in some detail across the four central case studies. By contrast, the conclusion is relatively brief in positing what is to be done — because flak is, indeed, a daunting problem. More information is readily available than ever before, but a significant share of it is strategically weaponized.

I will double down on my conclusion in the book that all-out commitment to divining the Truth needs to drive our politics and deliberations about the world around us.

Moreover, we cannot be seduced into the assumption that better internet "moderation," smatterings of fact-checking or technical solutions will deliver a miraculous, pill-like panacea to social problems that manifest themselves on media platforms. We will need to do this ourselves, with hard work and commitment.

If we want to make the world of media better, and to capture the textures of reality with less manipulation, we also need to operate on reality itself and make it better. In this view, life-long education, well-fed and housed citizens who possess iron-clad insurance against the vicissitudes of health and employment, are less readily manipulated than people trapped in an unjust, divided, and predatory social order. Let us fix what is wrong in the material world rather than conjuring more benign, mediated glosses on it.

I am nominally Catholic and graduated from a Catholic high school, along with living in a historically Catholic country and working long-term at our Jesuit campus. For me, Catholicism is more of a cultural identification than a theological matter.

Our campus in Madrid also attracts students and faculty from a range of confessional traditions that include "none of the above." Indeed, the university’s mission is clear, as it "Welcomes students, faculty and staff from all racial, ethnic and religious backgrounds and beliefs and creates a sense of community that facilitates their development as men and women for others." In that vein, the origins of the word "Catholic" have been translated as "universal" — an antonym to exclusive or sectarian. It is a strength of our campus and our cross-Atlantic university to be striving toward unity within diversity within an ethical scaffolding.

The content of the book also aligns with other features of our university’s stated mission. To wit, the book was composed within a framework of the mission’s "active and original intellectual inquiry," values that flak assays to degrade. One of the book’s case studies indeed orients to flak against universities and their function as workshops for knowledge and ladders of advancement for students from all backgrounds.

Favorite book: Orientalism by Edward Said (1979).

Favorite Film: North by Northwest, directed by Alfred Hitchcock (1959).

Favorite Films of the current decade: Beyond the Hills/Dupa dealuri, directed by Cristian Mungiu (2012) & Birdman, directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu (2015).

Favorite cities in Spain, besides Madrid: Burgos, Cáceres, Girona, Granada, León, Ourense, Salamanca, Seville.

Favorite cities in Europe not in Spain: Porto, Portugal and Prague, Czech Republic.

Number of class sessions I have not been able to deliver due to illness since I first delivered university courses in 1989: Zero.Write Stuff is an occasional series of interviews with SLU faculty and staff authors who have newly-published or forthcoming books. To submit your work for possible inclusion in the series, email Newslink.